Wildfires have beneficial effects on the landscape, but some wildfires just completely wipe out all life. Prescribed burning is one of the strongest tools we have to reduce fire intensity.

May 19, 2022

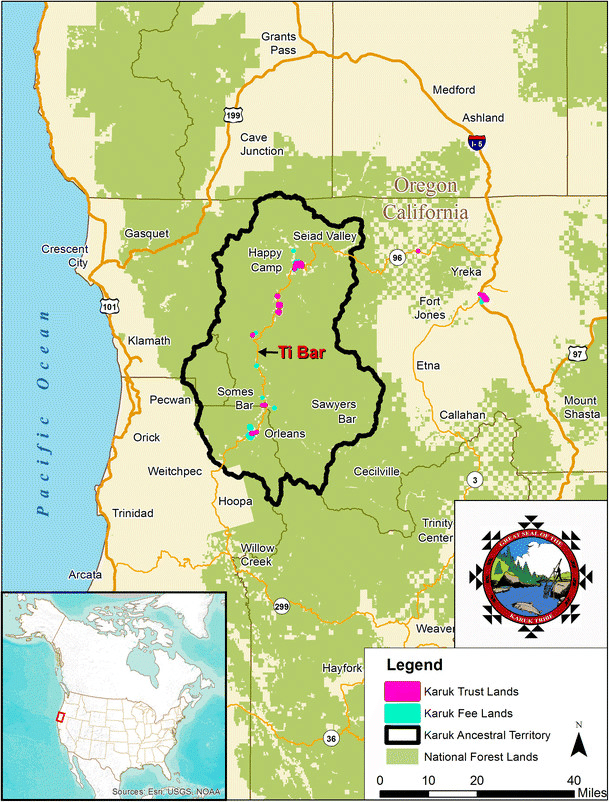

Much of the land that makes up the Klamath and Six Rivers national forests has been home to the Karuk Tribe since time immemorial. For decades, they have advocated for the return of their ancient burning practices to manage their land. And now, there is a pilot project under way to use fire to reshape damaged ecosystems.

For the tribe, there’s hope that the change in policy will restore the traditional Karuk lifestyle in the way fire restores their forests.

“The Karuk people evolved with the landscape, with the native plants and animals that share our homelands continuing to be a part of our daily lives for our well-being and survival,” said Analisa Tripp, collaborative stewardship program manager with the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources. “The practice of burning the brush every year meant we could rely on acorn groves for food and cultural materials.”

The tribe is part of a group of stakeholders called the Western Klamath Restoration Partnership that has put together a detailed restoration plan using a geographic information system (GIS) to analyze and prioritize the actions needed to return the land to balance.

A growing number of extreme fires have recently impacted the area. In 2021, the fire season stretched from mid-May through October, the longest on record, and in 2020, the Slater and Devil Fires burned 166,127 acres.

According to a new study, there were far more fire-resistant hardwoods when the Karuk Tribe tended the forest. The researchers consulted the tribe about their oral history and cataloged scientific evidence of past fires. They found that the tribe’s cultural forest-burning practice helped shape the region’s forests for at least a millennium prior to European colonization and that the forests then were more resilient.

The Karuk Tribe’s use of fire has connections to culture as well as sustenance. Fire revitalizes willow and hazel stands that send up fresh shoots, ideal as basketry materials. It causes the tan oak acorns to drop so they can be harvested and ground into flour. It also burns invasive plants that suck up rain and push out native food sources.

Wildfires have beneficial effects on the landscape, but some wildfires just completely wipe out all life. Prescribed burning is one of the strongest tools we have to reduce fire intensity.

Members of the Western Klamath Restoration Partnership are working together to prepare for prescribed burning. They are using location-aware GIS applications in the field to document which trees to keep and which to cut down for a more balanced landscape.

“It’s also about helping the species that are suffering on the landscape and adjusting the forest to what it would have looked like culturally and historically,” Tripp said.

The move to cultural burning can’t happen immediately because fuels have been increasing due to a fire deficit on the landscape. First, they must thin the forest, and they are using GIS analysis to make decisions about where and how they carefully crop the area.

The Karuk Tribe uses GIS to map the location of culturally utilized species of plants and animals. Their data layered on GIS maps is informing adaptation strategies and was used to help craft the Karuk Climate Adaptation Plan to preserve cultural resources, promote biodiversity, and mitigate catastrophic wildfires.

“The knowledge and data that are gathered by the field crews and brought into the GIS are used to understand the landscape,” said Christopher Weinstein, GIS specialist with the Karuk Tribe. “This helps provide more focused management of species of interest, for their revitalization and continued growth.”

The Karuk Tribe—known as the upriver people—never left their land, despite efforts to erase and assimilate them, criminalize their culture, and extract the vital resources they rely on.

“There were laws that basically allowed native Californians to be enslaved,” Tripp said. “People’s homes and villages were burned down. A lot of people were pushed out. But Karuk people have always been here, continuously occupying our homeland.”

The tribe saw their streams reduced to rubble to extract gold and dammed for energy to the point salmon could no longer be found there. Forests were logged and replaced with fir plantations, displacing the groves and meadows where they harvested native plants for food and medicine.

“We’ve used GIS to visualize some of the degradation of the landscape, such as the destruction of river bars with dredge mining and hydroblasting,” Weinstein said. “We’ve also mapped the plantations and past timber harvest practices that aren’t consistent with tribal values.”

Now, most of the extractive industries have come and gone in the Karuk territory, and there’s momentum to reset the land. The tribe recently received $4 million in funding to increase wildfire resiliency and minimize the vulnerability of structures.

“We have a vision of what we’d like the landscape to look like, but we’re still working out what it will take to get there,” Tripp said. “It’s a lot to come back from.”

Read more from the Karuk Wildlife Team’s interactive story. Learn more about how GIS is being applied to take climate action.